Overview

Students can be engaged with assessment and improvement in performance by innovative uses of feedback on assessment tasks to provide guidance on future learning. Anecdotally, many academic staff say that students pay little attention to feedback, while students say that the feedback they receive is unhelpful. Recent research has led to development of techniques for ‘closing the feedback loop’, so that students are supported to reflect on feedback and to use it to guide future learning with the aim of improving performance in later assessment tasks.

This section provides:

- An overview of research on engaging students with feedback

- Exemplars from different disciplines

- Practical tips for using feedback on assessment to engage students and improve performance.

Additions to the Assessment Policy:

- Formative assessment

- Summative assessment

- Assessment that generates timely and useful feedback

Formative/summative assessment

The revisions to the assessment policy include the importance of providing formative and summative assessment tasks, and the provision of effective feedback to guide student learning. Formative assessment refers to assessment activities that are designed to let students know how they are doing, to quickly reinforce learning, and to alert students and staff to the requirements of the subject and any shortcomings or misconceptions the students may have. Formative assessment can lead to remediation if it occurs early enough in a subject. Formative assessment may consist of in-class or online activities that are not graded, however it may also consist of a low-stakes task for which a grade is recorded. Early low-stakes formative assessment is recommended as it can alert students and staff to aspects of the unit where they need to focus more effort, while not penalising the student with a high enough percentage of the marks to put the student at risk of failure from the beginning. Summative assessment is graded, serving the traditional role of certifying the student’s level of performance. Summative assessment however can still play an important role in guiding student learning, depending on the nature of the task and the effectiveness of the feedback provided earlier in the subject. A balance of formative assessment, summative assessment that encourages active learning, and effective feedback can play a powerful role in guiding and supporting student learning to enhance performance in relation to the assessment criteria for the unit.

Considering assessment in this way is described as ‘assessment for learning’. This characterises assessment that meets the requirements to certify performance while also using assessment as a tool to encourage and guide the learning activity needed to meet the requirements of the subject. If students clearly perceive the in-depth requirements of the assessment task, such as levels of investigation, application, calculation, analysis, or diagnosis needed, they are likely to apply themselves to the required activity. Assessment is identified as the most powerful motivator of student effort, defining the actual curriculum for students (Ramsden, 2003, cited in Armstrong et al, 2015), so it is in relation to assessment that students will concentrate their activities. Assessment and feedback that makes the requirements clear in the nature and description of the task and guidance provided through feedback can be optimal in guiding and encouraging student learning. It has been reported that students who are unprepared academically benefit even more than others when they are engaged in a learning community through guidance and feedback (Sambell et al, 2013).

In the Assessment 2020 website, Boud et al (2010) assert that assessment has the most effect when:

- Assessment is used to engage students in learning that is productive;

- Feedback is used to improve student learning;

- Students and teachers become responsible partners in learning and assessment;

- Students are inducted into the assessment practices and cultures of higher education;

- Assessment for learning is placed at the centre of subject and program design;

- Assessment for learning is a focus for staff and institutional development;

- Assessment provides inclusive and trustworthy representation of student achievement.

These propositions begin with a focus on assessment activities that encourage productive learning and effective feedback, followed by associated classroom or online teaching and learning activities for guidance on assessment.

Importance of feedback

‘Higher education institutions are being criticized more for inadequacies in the feedback they provide than on almost any other aspect of their courses’ (Boud & Molloy, 2013). Consequently the provision of effective feedback is the subject of current research on assessment. A key point is that all assessment should help students to learn and succeed. The question is how do we transition from assessment as a measure of performance to assessment as a guide to effective learning? Boud and Molloy (2013) propose ways of positioning learners as seekers of feedback to improve their learning. This implies a different approach to feedback for academic staff and students. Anecdotally, academic staff often observe that students do not pay much attention to the feedback they have carefully crafted for them. This is understandable if students do not know what to do with the feedback they are given, and/or if it is not provided at a time at which students can act upon it. There may be an unwarranted assumption that students know how to improve as a result of feedback comments on their performance. Boud & Molloy (2013) suggest that students and teachers need to see the provision of feedback as a means of promoting active learning, by providing feedback in a timely manner to guide more effective learning, and encouraging students to reflect on feedback and use it to plan for improvement. Students may not know how to do this for themselves, so classroom and/or online activities should be used to guide this as a process.

The way that students engage with feedback is critical to learning. Feedback needs to provide guidance for improvement in relation to the assessment criteria. This communicates that the way assessment is conducted is according to criteria, and not a secret or a way of tricking or trapping the student. If students are given guidance on how to reflect on the feedback they have been given on their assessment, either in class or online, in relation to the criteria, they should be able to identify issues they can address. If the performance required is clear, students can make a plan, again with guidance, on how to improve their performance for the next assessment task in relation to the assessment criteria. In this way students can know how to act on feedback to consciously improve their performance. To enable students to do this, feedback needs to reach the student in time to act on it, and assessment tasks need to relate conceptually to each other.

Timely Feedback

Students should be given a clear indication, in the learning guide, as to when feedback will be provided for each task. Prompt feedback ensures that students haven’t lost track of the work they did for the assessment task, and that they have time to reflect and act on the feedback before the next assessment task is due. A turnaround time of up to a maximum of three weeks for marks and feedback is recommended.

Assessment tasks that promote learning

Effective learning can be supported by the nature of the assessment tasks. Carless (2015) stresses the point that summative assessment can be learning oriented, if the task:

encourages deep rather than surface approaches to learning and when it promotes a high level of cognitive engagement consistently over the duration of a module. The processes of working towards well-designed summative assessment can also afford opportunities for formative assessment strategies, such as peer feedback, student self-evaluation and related teacher feedback (Carless 2015, p964).

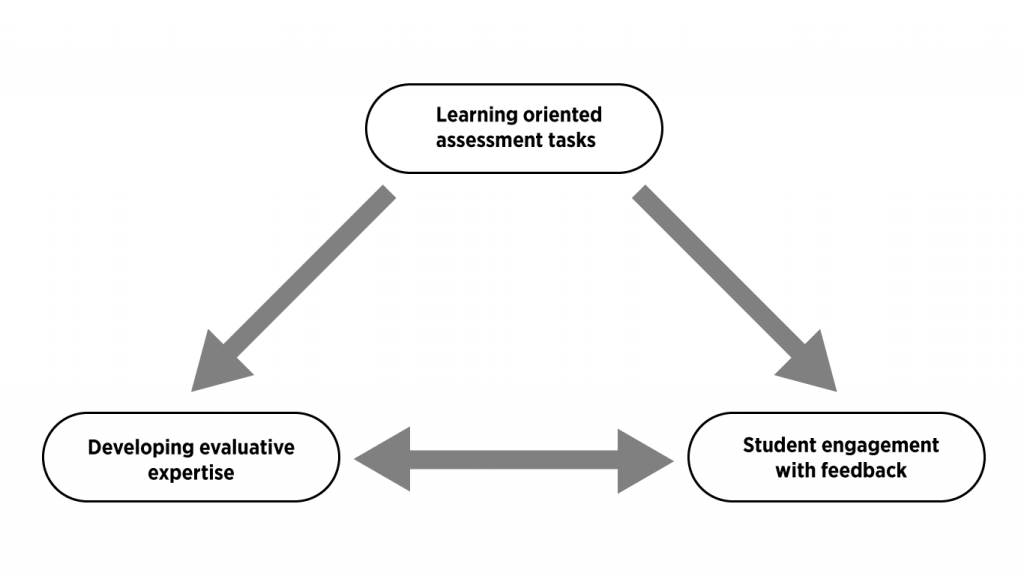

Figure 3 illustrates an overall process.

Figure 3. A Model of Learning Oriented Assessment (based on Carless, 2013, p965)

The diagram encompasses three related factors; the nature of the assessment task, the way students engage with feedback, and the development of evaluative expertise by students. The latter can be developed over time by learning how to use feedback for effective guidance and planned improvement repeatedly until a capacity for self-evaluation is developed. The nature of the assessment tasks may also support development of the student’s own self-evaluative capability. Carless (2013) suggests assessment tasks based on ‘real-life’ problems, contextualised to the discipline, as a means of promoting student engagement with learning and assessment feedback that can lead to the development of evaluative capability by students.

Examples of the process provided by Carless (2013) include:

History

In Making History, the subject coordinator developed the students’ understanding of how historical interpretations are constructed through multiple complementary assessment tasks. This involves a focus on providing tasks that relate to what it means to be a historian, including techniques of critique, contestation, competing discoveries and interpretations of the meaning of the past. The assessment tasks include:

- A museum visit or material ‘scavenged’ from the Internet to find source material;

- Assessed participation in weekly tutorials;

- Assessed weekly response tasks;

- A 40% individual project, assessed as:

- Draft (10%)

- Final Project (30%)

- The final project may be presented as a 3000-word piece of writing, a podcast, wiki, or in another technical format.

The subject coordinator offers students an optional workshop on how to tackle the project assignment. While every task has an opportunity for feedback, both from student peers and the teacher, the draft stage of the individual project is specifically included to provide guided feedback on the task.

Students enrolled in the subject gave favourable reviews on the value of the assessment tasks.

Business

In the Business subject example, students were assessed on a written assignment on a business case study, an oral presentation of product ideas, and participation including oral classroom and written online contributions. To encourage students to enhance their performance the teacher video recorded examples of oral presentations and replayed short extracts, followed by guided reflective discussions, to illuminate characteristics of good business presentations. The teacher also engineered in-class feedback dialogues about the process of learning, and on the processes in relation to particular assessment tasks.

The above examples illustrate how learning tasks can be designed to engage students and encourage learning, and how feedback can be used as feedforward to guide students to optimise learning in the subject. As he points out, an important aim is the third point of the triangle in Figure 3 – to develop the student’s capability for self-evaluation, so that the students can internalise their own process for continuous improvement.

Discipline specific approaches

Carless (2013) provides a range of examples from other disciplines also, to illustrate ways of using assessment and feedback to engage students in active learning, and to promote and guide student learning through engagement with feedback. For additional case studies, see Feedback for Learning: Closing the Assessment Loop.

Engaging students with feedback

Students need to be encouraged to engage with feedback and to use it for guidance. Some actions that are critical for this are:

- Students must see the importance of feedback. Explain the purpose of feedback in relation to the assessment criteria. Students need to know that feedback is telling them something that is important and useful to them, and why they should pay attention to it.

- Students need to receive helpful feedback. This must be timely. Comments on performance may be useful for justifying the mark the student has been given for the assessment task, however this may not provide guidance. If we want students to seek and pay attention to feedback then it must provide helpful guidance for the next assignment – feedforward in other words.

- Students need to know how to use feedback. Either as a classroom/tutorial activity or online, arrange activities so that the students can:

- Review the feedback they have received in relation to material such as exemplary answers, the assessment rubric, the expectations of the task.

- Students must know how to use feedback to improve their performance. Following on from the review activity, at a point closer to the next assignment, set up an activity to enable students to reflect on what they learned from the previous feedback, and how they will act to improve their performance as a result. By consciously planning to improve as a result of feedback, students can begin to develop a capacity for self-evaluation that will be valuable for their future study.

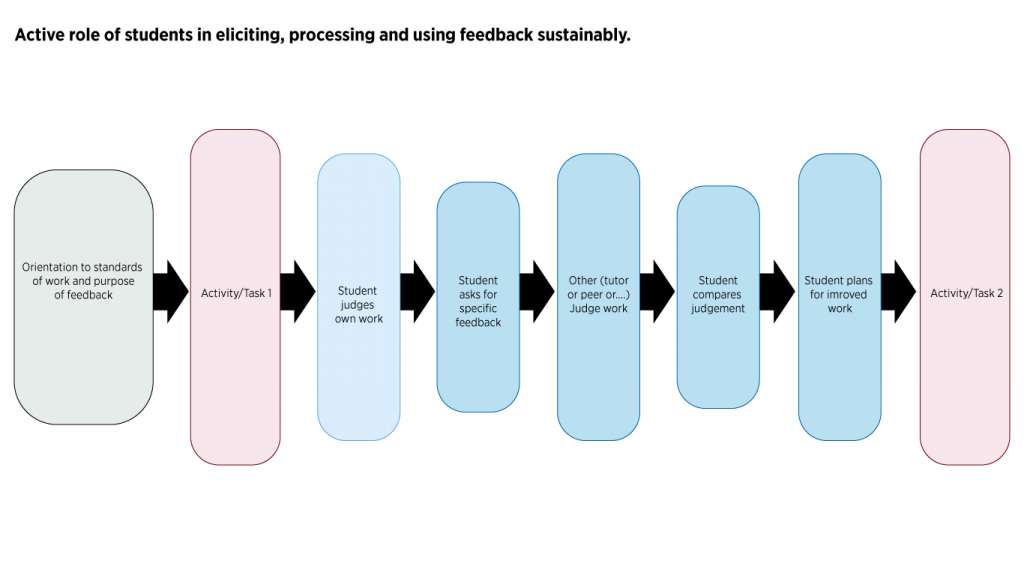

Boud (2017) illustrates the process in Figure 4.

The above process begins with an orientation towards standards and expectations of the first assignment before submission. This process can be included in tutorial activities, flipped classroom activities, or online learning activities so that students have the opportunity to learn how to reflect on feedback. Reflection may include reviewing the details of the assessment rubric in the learning guide. Additionally, students need support on how to discuss feedback with peers and tutors, and how to use feedback as feedforward by planning a way to improve future performance. This should be based on guidance obtained from feedback on a previous task.

Resources

Armstrong, S., Chan, S., Malfroy, J., and Thomson, R. (2015). Assessment Guide: Implementing criteria and standards-based assessment. 2nd Edition, University of Western Sydney.

Boud, D. and Associates (2010). Assessment 2020: Seven propositions for assessment reform in higher education. Sydney: Australian Learning and Teaching Council. https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/Assessment-2020_propositions_final.pdf

Boud, D. and Molloy, E. (2013). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: the challenge of Design. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 38, 6, 698-712.

Boud, D. (2017). Rethinking and redesigning feedback for greater impact on learning. Centre for Research in Assessment and Digital Learning, Deakin University. Workshop presented at WSU, October 23rd, 2017.

Carless, D. (2015). Exploring learning-oriented assessment processes. Higher Education 69:6, 963-976. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10734-014-9816-z

Feedback for Learning: Closing the Assessment Loop Case Studies

Nicol, D.J., and McFarlane-Dick, D. (2005). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education. http://www.psy.gla.ac.uk/~steve/rap/docs/nicol.dmd.pdf

Sambell, K., McDowell, L., and Montgomery, C. (2013). Assessment for Learning in Higher Education. Routledge, London & New York.